For Pride Month, I’ll be sharing pop culture works like literature, film, television, and music to celebrate queer culture.

Vito Russo was the leading queer film critic and AIDS activist of his time. When he died of AIDS in 1990, he left behind a moving and inspirational legacy, one the most enduring was his 1981 book, The Celluloid Closet. That work was a landmark look at queer history in cinema, specifically Hollywood film. The book was re-released in 1987 at the height of the AIDS crisis, catching up to what was happening in queer America at the time.

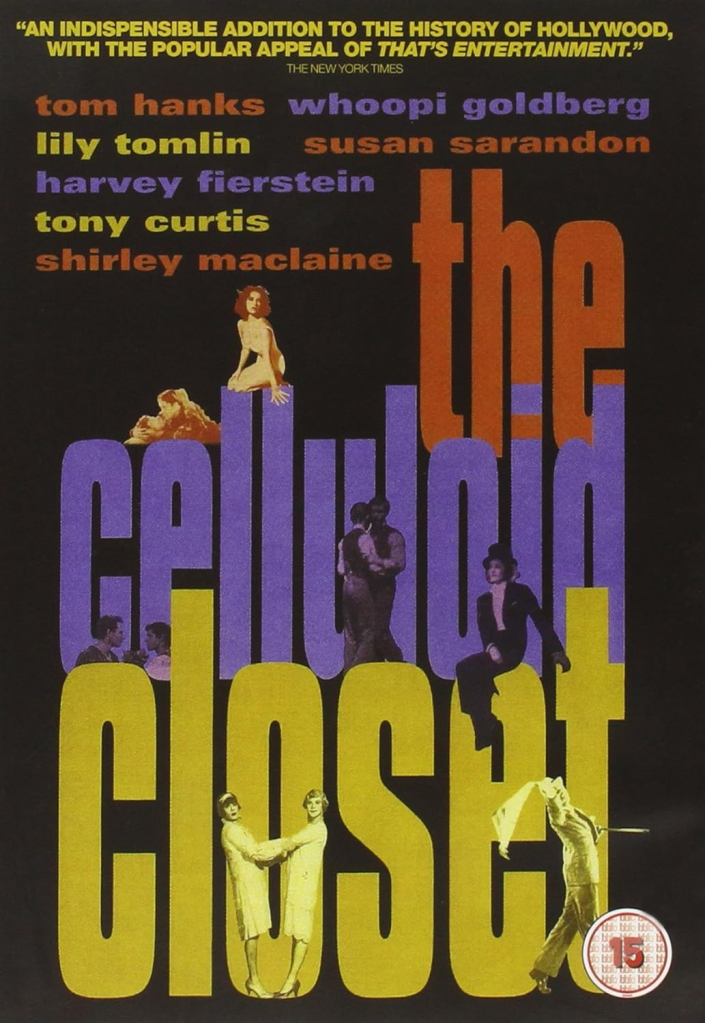

In 1995, directors Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman saw their film adaptation of Russo’s book released to great acclaim. The film picked up on queer cinema since the book’s publication and the author’s death, including New Queer Cinema as well as mainstream films like Longtime Companion (dir. Norman Norman René, 1995), Mrs Doubtfire (dir. Chris Columbus, 1993), and the Oscar-winning Philadelphia (dir. Jonathan Demme, 1993). Interviews with stars, screenwriters, and film theorists are included in The Celluloid Closet and the resulting film is a lively conversation among some great minds.

The Celluloid Closet is a fantastic film. Sometimes it’s quite funny: there’s a scene from the Howard Hawks 1948 Western, Red River, in which Montgomery Clift and John Ireland trade smirky double entendres as they practice shooting targets, each admiring the other’s ‘gun’. Sometimes it’s very sad: having to rewatch scenes of queer characters twist in self loathing is hard, most notably when watching Shirley MacLaine suffer piteously in the William Wyler 1961 melodrama The Children’s Hour (MacLaine’s contemporary interviews betray a strange ignorance of queer self-hate in the 1960s, though). Because this film is released in the early 1990s, we see a thrilling optimism, especially evident in the growing representation of queer life in mainstream cinema, but that progress is mitigated by the tragic spectre of AIDS, which is illustrated by the examples of Demme’s and René’s films, both of which tackle the illness and its social consequence in an unflinching matter. We also see lots of representation of drag in The Celluloid Closet, and it’s some of the most interesting and engaging parts of the film: we see all kinds of drag, whether it’s the queer drag of La cage aux folles (dir. Édouard Molinaro, 1978) or Stephan Elliott’s 1994 classic The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert; or the situational drag of films like Billy Wilder’s 1959 masterpiece Some Like It Hot which uses drag as a way to create chaos and disorder for its characters in a farcical universe. Alongside these examples of queer representation, we also see the backlash, when queer folks are depicted as depraved, predatory monsters in films like The Silence of the Lambs (dir. Jonathan Demme, 1991), Basic Instinct (dir. Paul Verhoeven, 1992), and Joseph Mankiewicz’s overheated 1958 melodrama Suddenly, Last Summer. In light of the current legal and cultural backlash we’re seeing in UK and USA politics, these instances are depressingly relevant again.

One of the things that strikes me each time I watch the film is how much cinema is crammed into 107 minutes. It’s a lot of history, almost a century, and one film isn’t up to capture the whole story. But it packs a wallop. There should be a sequel, because in the thirty years since The Celluloid Closet, queer cinema has seen so many changes and we’ve yet to even begin a serious talk about trans representation in cinema, though Netflix did a commendable job with its documentary, Disclosure (dir. Sam Feder, 2020).

A few years ago, I wrote up a piece for Bright Wall/Dark Room, “Coming Out of The Celluloid Closet.”

Leave a comment